A blog from the perspective of the Curator, Jan Freedman, Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery highlighting risks to collections, in particular natural science, and how UK museums can help each other to solve problems, identify and prevent risk.

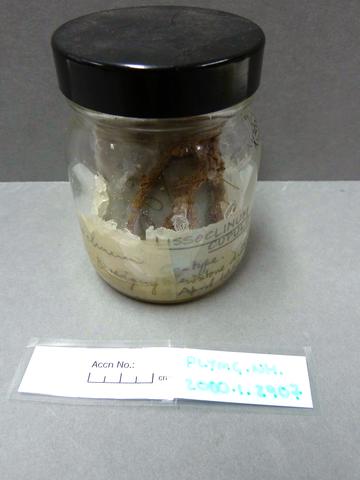

Type specimen of a spoon worm in the spirit collections at Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery. The specimens was discovered in the collection after a collections review, and has since been fully conserved].

Displays, outreach events, research, conservation and talks are some of the well-promoted, glamorous work a museum curator may have to carry out. Even less exciting tasks like documentation, digitisation, databasing, and cleaning storerooms are mentioned in blog posts and publicity.

Being a museum curator is incredibly fascinating, rewarding and exciting, but it is not without risks.

The one thing that underpins every curator’s work is, of course, the collections. From the smallest insect to the largest fossil, natural history curators often care for the most diverse types of collections in a museum.

Natural history curators care for large and small specimens. Entomology collections can number in their thousands.

Image © Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery]

Curators have a responsibility for all the collections in their care and this can be a surprisingly risky business. Behind closed doors, curators are ensuring the safety of the nation’s historic treasures so they can be used and enjoyed both today and in the future.

Risks to collections have traditionally been called the ’10 agents of deterioration’ (developed by Dr Robert Waller*), although I will argue for one more. These are the main threats to collections and all curators are trained to ensure that specimens, whether in the store room, on display or on loan, are safe.

The 10 agents

The risks can be broadly grouped into three categories:

- Disaster: Events that, although rare, can have catastrophic effects on museum collections (fire, flood, and physical forces)

- Unavoidable risks: Risks to specimens and collections that are naturally occurring (pests, light, temperature, and humidity)

- Avoidable risks: Risk to collections due to human activity (theft/vandalism, pollutants and custodial neglect)

Disaster

These can be the most devastating of events and can destroy entire collections.

Fire can smoother specimens in soot, and destroy labels and any paper associated with the specimen. In worst case scenarios entire collections can be lost (for example, herbaria, taxidermy, entomology). Precautions are relatively cheap and easy to implement, such as fire doors, regular fire alarm checks, annual PAT testing of electronic equipment, and clean offices and store rooms.

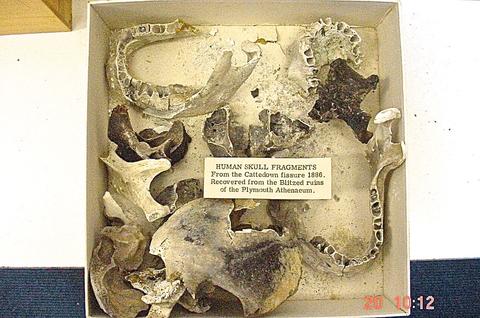

Severe bombing during the Second World War destroyed and severely damage collections across the country. These hominin remains from Cattedown, Plymouth, were rescued from a fire during the Plymouth Blitz. Image © Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery

Flooding is, sadly, a fairly common disaster, mainly due to old pipe systems in many museums. Burst pipes and blocked drains are the main causes of floods. It can also occur after a fire due to sprinkler systems or from water used to extinguish fires. Labels can peel off specimens, become unreadable or break apart. Many specimens will need extremely careful conservation. Flooding is unpredictable and can happen anywhere. Precautions need to be in place for this type of disaster (see Disaster Planning at the end).

Collections are at risk from physical forces on a daily basis. These can range from moving a box of specimens from one place to another to the other extreme of an earthquake. In the UK earthquakes are very rare, but they do happen. Good packaging of specimens will reduce any damage to specimens in drawers or boxes. Acid free tissue can be used to nest specimens. Plastazote (an inert closed cell cross-linked polyethylene foam) cut-outs can be used to support a specimen in a box and reduce movement.

Robust specimens may be packed fairly well in clear boxes to reduce the amount of movement. Acid free tissue ‘nests’ can be made to pack specimens, or Plastazote can be cut out to hold a specimen. Image © Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery

Unavoidable Risks

There are many risks to collections that are naturally occurring and these can have huge effects on collections. Fluctuating temperatures from changes in seasons, heating malfunctions, or simply leaving a door open, can cause damage to specimens. High temperatures can cause drying and cracking to many collections (shales, sub-fossils, taxidermy, entomology, herbaria, and others). Low temperatures can cause high humidity, which can have additional effects on the collections (see below). Controlled environments which are monitored can keep temperatures at the required levels (ideally between 15oC – 22oC).

High levels of humidity (rH), or too little, in a store room or gallery can damage collections. High humidity can cause mould growth on specimens. Low humidity can cause specimens to begin to crack. Ideal rH conditions should be between 45% and 55% (this will depend on the type of collection in the store rooms, and some collections may require slightly higher or lower humidity levels). A humidifier in the store room or gallery can assist in controlling the conditions to the required levels. Fluctuations in humidity are extremely important: rapid fluctuations are more damaging that high or low levels in themselves.

High levels of light will cause fading in taxidermy, herbaria, many entomology collections and on original labels. Generally, collections store rooms don’t have windows, and lights are only on when someone is in there. Specimens are more at risk from being on display if sunlight comes through gallery windows or there are bright lights inside display cases. Although feathers may be repainted, the original colour is permanently gone. UV filters can be placed on windows or display cases to reduce UV light levels, and using LED bulbs inside display cases can reduce fading. Regularly changing specimens on display also ensures they are not exposed to light for too long.

Pests come in all shapes and sizes and can literally eat their way through collections. Even geological collections are at risk, as pests can eat the paper labels and the glue which attaches the number to the specimen. Simple mechanisms can reduce pests. Store rooms and galleries should be kept clear of food and drink and have controlled environments which are not suitable for most insect pests. Pest traps (called museum traps) can be placed around the museum and monitored to assess the pest activity. Specimens in galleries and store rooms can show signs of pest damage, such as loss of fur or feathers or by a little pile of dust underneath the specimen (insect frass). Pests can be removed by placing the specimen in a sealed bag and freezing around -22oC for at least a week.

The pile under the specimen which looks a bit like sawdust, is a result of a pest eating this bumble bee from the inside. Image © Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery

Avoidable risks

Store rooms and galleries are at constant risk of pollutants. Work carried out in, or near, a space where specimens are can leave debris contaminating specimens. If galleries are being refurbished, all specimens on display should be removed or protected before any work begins. Dust is probably the most common pollutant. This can be reduced by regular cleaning of store rooms, and ensuring any work that needs to be undertaken on a specimen is carried out in a separate space. Vibration from drilling and building work can also be problematic.

Museums have, sadly, been subjected to theft and vandalism. More recently the attempted thefts of rhino horns on display have caused concern. Replacing real specimens with replicas reduces the risks (and labelling why it is a replica also raises awareness of these issues). Security cameras, staff presence in galleries and regular training for staff will help reduce the threat of theft or vandalism.

One of the worst types of risks is custodial neglect. Here, all the risks above may happen and because they are unchecked, they can slowly turn a specimen to dust even though the curator is in the building. With many restructures, many curators are now taking care of a wider range of collection areas. This can result in curators neglecting those areas they are least confident in. Training and networking for staff is essential to ensure they are able to safeguard the collections in their care.

Disaster Plan

All museums should have a disaster plan or emergency plan. This will outline the procedures should a fire, flood or other disaster happen. Included within the disaster plan are the points of contact, floor plans, risk assessments, emergency equipment, suppliers and utilities, and damage record form. One of the most useful pieces of information for the fire service is the ‘grab list’: the specimens that should be rescued first if there is an emergency.

Each store room should have a place which is close to the door storing their ‘grab list’ specimens. Here, the sprit specimens are packed well in Gratnell trays so the entire tray holding the specimens can be removed during an emergency. In the event of a fire, no one is to enter the spirit store. Image © Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery

An 11th Risk?

The Collections for All ‘RISK: Real or perceived?’ workshop was recently held at the Natural History Museum, Tring. It was a scoping workshop with 24 attendees from national, regional and university museums, together with representatives from Arts Council England and National Museum Directors' Council. The purpose of the workshop was to discuss RISK and analyse what the sector could be sharing on the subject of risk. One of the biggest risks highlighted was that museums throughout the UK are not engaging enough with each other. We need to open this out more and ensure that workshops like these are open to independent and more regional museums too. Specialist staff in national and regional museums are very willing to share their knowledge and best practice. The question in the workshop was raised, how can knowledge exchange be facilitated further, particularly regarding risk? So, if you are a museum who is just thinking about risk and wondering where to seek help and expertise, hopefully this blog post is a start.

Here are my top five things to think about:

-

Ask for help

Don't be afraid to ask colleagues in other museums for help or advice. You might not know who to ask or feel that you can, so have a search in museum networks (NatSCA, GCG, GEM, Arts Council England, Federations, Museums Association, Museum Development etc.) or just pick up the phone. In my own experience, curators across the country have been more than happy to help with problems. Some have helped me identify a strange pest and what I can do to protect specimens, and others have helped me with conservation issues. Natural history collections are riddled with potential problems: if you see some strange white powder on a taxidermy specimen and you don’t know what it is, contact someone (this is arsenic, used on specimens before 1964). If you have some radioactive minerals, don’t just put them in a box and leave them (sorting them out is easier than you think!). I am extremely grateful for the advice I have received. It has added to my own knowledge and enabled me to help other museum staff with similar problems.

-

Look out for training

There are many training networks that provide workshops and sessions. Look out for ones at subjects that are relevant to risk. Subject specialist networks, Museums Association and regional museum development organisations provide such training, as do Associated Independent Museums (AIM). The best part of external training and conferences is that you meet with other colleagues and can share problems and solutions. Get involved, and stay in touch with the networks and don't be afraid to ask for subjects to be covered in training.

-

Offer support and advice

Don't forget to try and share your knowledge and expertise as much as possible too. We cannot be an expert in everything – collections are just too vast to allow that to be possible. On mailing lists (such as the NatSCA JISC Mail for example), I often see emails seeking advice. I help where I can, and if I don’t know, I suggest a colleague who is likely to know. I think it is so important to share our knowledge where we can. Curators, particularly in smaller museums, are often working on hugely diverse collections, many out of their comfort zone. By offering advice, you are supporting the safety of those collections and giving the curator the confidence to use them to their full potential.

-

Visibility: knowledge sharing

Try to write up projects you have been working on. You can be very detailed for subject specialist Journals (like the Journal of Natural Science Collections, or The Geological Curator). Or you can write more informal pieces for blogs. It may not seem interesting to other people, but writing about an education programme you have done, or conservation of some specimens not only promotes your institution and collections, but shares your skills with others. I write for my own blog about museum issues, and am a guest blogger for Museums and Heritage. I regularly use Twitter to stay in touch with colleagues around the world, keep up to date with the latest museum issues, and promote our collections. Twitter is really a wonderful community where you can interact with colleagues, share your own knowledge, and learn from others.

-

Advocacy

My suggested 11th risk; we are not engaging with each other fully, could be the most deadly of all. National museums need to work together to promote collections, and offer support and advice for staff in the regions. And regional museums need to shout more about the work we are all doing and the amazing collections we have.We need to ensure we don't forget to advocate more to each other to share and to try and incorporate this in our policies and agendas.

If you are concerned about any of your natural history collections, please contact the Natural Science Collections Association (NatSCA), or the Geological Curators Group (GCG) for advice. Or, please do feel free to get in touch with me in the first instance (jan.freedman@plymouth.gov.uk).

By Jan Freedman, Curator of Natural History, Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery

*'10 agents of deteriotian' : Dr Robert Waller, formerly of the ICC (Canadian Institute of Conservation) and Canadian Museum of Nature*. Publication Cultural Property Risk Analysis Model was published by Goteborg University in 2003 as volume 13 of their Studies in Conservation.

Add new comment